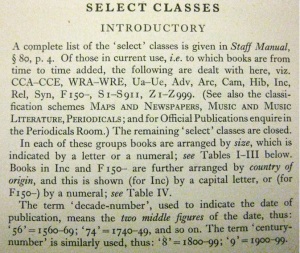

Readers might remember that one strand of decolonising our collections in response to Russia’s war against Ukraine, as outlined in an earlier blog post, was about classification. As explained then and long known by readers using our open-shelf collections, large parts of the UL’s classification system still strongly reflect the times and attitudes of empire. There’s a lot of work to be done here just to tease all the various threads out.

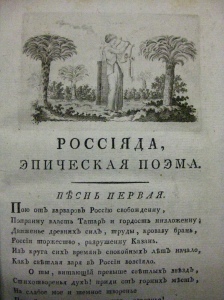

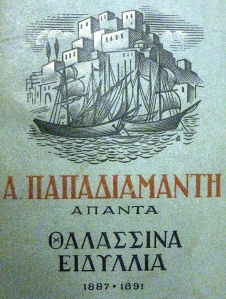

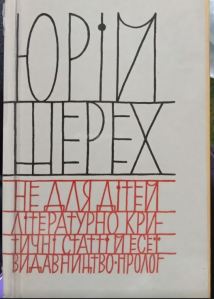

Taking the focus back to Ukraine specifically, I have taken a preliminary look at the Ukrainian component in the “Russian literature” classes – 756 and 757. These classes, meant to contain Russophone literature only, was in practice also the destination for Ukrainophone literature too until the introduction in 2011 of a separate class (758:6) for the latter. There was always a different classmark for “Other Slavonic” (758:8) for languages without their own classmark, but unfortunately Ukrainian appears to have been placed standardly in Russian for decades.

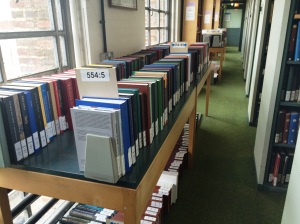

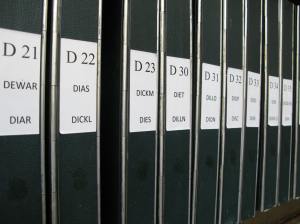

Today’s initial work has been to work out what at least roughly what amount of books it is that we might potentially move, reclassify, and re-label. Here are the initial results.

- 756 contains 252 titles in or translated from Ukrainian

- 757 contains 190 titles in or translated from Ukrainian

So far, so relatively straightforward, if still representing quite a lot of work (I think it would be a challenge to deal with one book in 10 minutes, given all the things that would need to happen, so those figures alone would mean 2 weeks full-time as a minimum). What is missing here, though? Continue reading “Decolonising the old classification of Ukrainian literature”