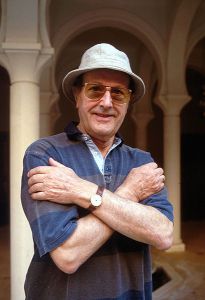

Very few artists can boast a career spanning more than 80 years and even fewer can claim to have been at their artistic and critical peak when approaching, and indeed reaching, their own centenary. However, both of these things were true of Manoel de Oliveira, arguably Portugal’s greatest filmmaker and unquestionably cinema’s most longstanding director, who passed away on April 2 this year at the age of 106.

Manoel Cândido Pinto de Oliveira was born on December 11, 1908, in Porto and began his filmmaking career in 1931 with a 20-minute silent documentary about his home city’s famous river, Douro, faina fluvial.

Douro Faina Fluvial from joão sobral on Vimeo.

His first full-length feature was the 1942 children’s parable, Aniki-Bóbó (see Manuel António Pina’s study of the film at C203.d.3820). In common with almost all of Oliveira’s subsequent works, this was a literary adaptation (in this case of a short story by José Rodrigues de Freitas), which came to be regarded as one of Portugal’s most significant films, as well as an early example of the neo-realistic style that went on to play such a huge part in European cinema.

However, whilst Oliveira’s French and Italian counterparts achieved international acclaim and success, he found his creativity stifled by Portugal’s repressive Estado Novo government. It was not until the regime was toppled in the 1970s that he began directing again in earnest.

From then on, his productivity was unmatched, particularly from the mid-1980s onwards, when he began working with actors and other collaborators from outside Portugal.

Of particular note during this period were: 1995’s The Convent, an adaptation of a novel by Agustina Bessa-Luís (whose work Oliveira based four of his films on), starring Catherine Deneuve and John Malkovich; the final screen appearance of the great Marcello Mastroianni in 1997’s semi-autobiographical Voyage au début du monde; Belle toujours, his 2006 sequel to the classic Belle de Jour (to whose director, Luis Buñuel, Oliveira was often compared), starring the original film’s Michel Piccoli.

Perhaps Oliveira’s most emblematic film, however, was his 1985 adaptation of Paul Claudel’s play Le soulier de satin. Running to seven hours long, this work dealt with many of the themes central to the director’s oeuvre, such as religion and sin, history – particularly in relation to colonialism and imperialism – and the troubled relationships between men and women.

The film won the Sergio Trasatti Award at the 42nd Venice International Film Festival, but surely none of the jury at that event could have predicted that Oliveira would return to the festival almost 20 years later (and well into his 9th decade) to win the Career Golden Lion in 2004.

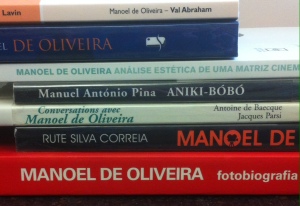

For such a highly regarded, prolific and longstanding director, relatively little has been written about Manoel de Oliveira over the years. As with many of his fellow filmmakers operating on the margins of the mainstream, his work has probably been best received and studied in France and Italy. Consequently, Cambridge University Library holds a number of titles in French and Italian about the director:

- Val Abraham de Manoel de Oliveira : l’illusion comme métier / Mathias Lavin (2012.7.2344) [dealing with another Bessa-Luís adaptation]

- Manoel de Oliveira : il visibile dell’invisibile / Bruno Roberti (C203.d.2635)

- Parole et le lieu : le cinéma selon Manoel de Oliveira / Mathias Lavin (415:3.c.200.1997)

- Manoel de Oliveira / sous la direction de Michel Estève et Jean A. Gili (415:3.d.200.91)

- Conversations avec Manoel de Oliveira / par Antoine de Baecque et Jacques Parsi (9007.c.4950)

The UL also holds the last-mentioned title in a Portuguese version (415:3.c.95.505) and it shows Oliveira to be a willing and vibrant conversationalist, still full of creative spark at an age when most filmmakers would have long since retired.

Indeed, Oliveira was one of the very few people working in film whose career spanned every distinct era of the art-form. One can get a sense of the length and breadth of this career in some recent Portuguese acquisitions, Rute Silva Correia’s Manoel de Oliveira : o homem da máquina de filmar (C209.c.9323), Manoel de Oliveira : análise estética de uma matriz cinematográfica (2014.8.5718) and Júlia Buisel’s 2002 “fotobiografia” of the director (2015.12.254).

However, Manoel de Oliveira contributed far more to world cinema than his longevity alone. Few filmmakers were more accomplished at transferring the qualities of literature to the medium of film, nor at conveying a sense of history and its lasting effects and importance. Over the course of his long career Oliveira developed a singularly measured and thoughtful cinematic style, leaving a body of work that is almost unparalleled amongst directors. Hopefully in the years to come, interest in and study of his work will continue to grow.

Chris Greenberg