Juan Latino (ca. 1517-ca. 1594) was born most likely in Baena (southern Spain), descendent of Guinea born parents. He was the first Afro-European to write in Latin and thus, have a literary career. In fact, he was called “Latino” for his mastery of that language. We should not forget that slavery was common at the time in Europe (see 532:8.b.200.1).

The fascinating story of Juan Latino is for Professor Aurelia Martín Casares (Universidad de Granada) an example of the triumph of wisdom (see C213.c.3056); he was able to break prejudices and social conventions in a somewhat rigid early modern society. In this story the noble family to whom he belonged, played a crucial role in helping make possible his exceptional achievements. Martín Casares compares Latino with the American abolitionist writer and orator Frederick Douglass (who escaped slavery in the 1830s), but makes the point that Latino lived three centuries earlier than Douglass.

Latino was the slave of the 3rd Duke of Sessa, Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba – grandson of the famous Spanish general who shared his name, the so-called The Great Captain. Fernández de Córdoba and his slave were of a similar age, so both grew up together and had the privilege of receiving an education. Latino could well have been the son of a male member of the family, even the 2nd Duke of Sessa himself, Luis Fernández de Córdoba. Gonzalo was a patron of the Arts and noticed Latino’s talent in that field, so he financed his education at the University of Granada. Latino obtained a bachelor’s degree in arts in 1546 and later became master or professor at the university. The Archbishop of Granada, Pedro Guerrero appointed him to the professorship of Arts.

Granada was then the most multiracial city in Spain and had been the last bastion of Moorish Spain (Nasrid Kingdom of Granada). As a result, there was a population of moriscos in the city (forced converts, descendants of Muslims). In fact, in Latino’s lifetime there was a second Moorish rebellion (Rebellion of the Alpujarras, 1568-71) in some areas of the Kingdom of Granada. The non-acceptance of the limitations imposed on the Islamic cultural traditions of the moriscos, in addition to the already banned non-Christian religious practices, was the origin of the rebellion. The moriscos were dispersed to other territories and eventually expelled from the country by the beginning of 17th century.

Latino married a noble woman, Ana de Carleval and they were one of the first legally recognised mixed race couples in Spain, having five children. The family lived in the Christian centre of Granada and had servants. According to a population census of the city, dated 1561, there were 51 slaves living in their parish (see C213.c.3056).

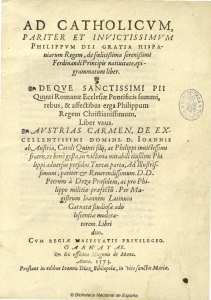

Interestingly, as Martín Casares points out, he is never described as black or as a freed slave in the contemporary documentation. In fact, he was a proud man who could even speak ironically about powerful (white) men of the time. He published two volumes of poetry printed by Hugo de Mena (Granada, 1573 & 1576). In the first one we find his main work Austrias Carmine, epic poem in honour of John of Austria, to commemorate the victory at the Battle of Lepanto (see The Epic of Juan Latino, ebook). In addition, he maintained for years a complex legal dispute concerning an economic obligation (or mortgage) associated with the previous owner of his house. So, he was a self-confident man who defended his interests with determination in various trials.

Latino had a long academic career and died in old age ca. 1594. Sometime after his death, both Miguel de Cervantes and Lope de Vega referred to him in writing. The first, putting Ladino as an example of an astute man in a satirical poem belonging to the preliminaries of the first part of Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605); the second, because he was under the protection of the 6th Duke of Sessa, and declared that he wanted to be his “white Juan Latino”. In addition, Diego Jiménez de Enciso wrote a comedy based on Latino’s life (1652). Furthermore, King Phillip II of Spain commissioned a portrait for his gallery of illustrious men at the Royal Alcázar in Madrid. The Portrait of an African man by Jan Mostaert, depicting a richly-dressed black man is an example of a similar contemporary painting.

Despite all this, Latino has been for a long time a rather obscure figure, who keeps attracting the attention of the researchers nowadays. As a result, recent research has cast new light on his life and work. The story of Juan Latino is so remarkable that it deserves to be better known. I find it surprising that no filmmaker has ever wanted to tell us his extraordinary story.

Manuel del Campo

Further reading

Earle, T.F. & Lowe, K.J.P. (eds). Black Africans in Renaissance Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. 538:2.b.200.1

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. & Wolff, Maria. “An Overview of Sources on the Life and Work of Juan Latino, the ‘Ethiopian Humanist”. Research in African Literatures: The African Diaspora and its Origins, vol. 29, no. 4, 1998, pp. 14-51. Full text.

Martín Casares, Aurelia. Juan Latino, talento y destino: un afroespañol en tiempos de Carlos V y Felipe II. Granada: Universidad de Granada, 2016. C213.c.3056

Id. Who was Juan Latino? Slavery in Early Modern Europe. UGRmedia, Youtube (10 min).

Rigaux, Maxim. “¿Servir con la pluma?: el efecto espejo en el Austrias Carmen de Juan Latino”. Millars: Espai i historia, vol. 47, nº 2, 2019, pp. 39-53. Full text.

Sánchez Martín, José Antonio y Muñoz Martín, María Nieves. “El Maestro Juan Latino en la Granada renacentista. Su ciudad, su vida, sus protectores”, Florentia Illiberritana, n° 20, 2009, pp. 227- 260. Full text.

Wright, Elizabeth R. The Epic of Juan Latino: Dilemmas of Race and Religion in Renaissance Spain. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016. Ebook version.