In a previous blog post, we talked about series of caricatures held in Cambridge University Library and other collections (such as Heidelberg University Library) depicting food shortages during the 1870-1871 siege of Paris. The Parisian diet was considerably and disturbingly altered and extended during this time, as people resorted to eating rats, cats, dogs, and horses. The current lockdown, due to the COVID-19 outbreak, with obvious economic consequences, is predicted to increase social inequalities, despite government measures such as the furlough scheme or the extension of free school meals vouchers over the summer holidays. Did the siege of Paris level or increase social differences, and how were they perceived by contemporary caricaturists? Satirical prints specifically targeted the way privileged classes coped with the situation of penury and food shortages. The relative suffering of the wealthy, bourgeois or aristocrats, is treated humourously in many of the caricatures produced at the time. They stress the fact that, though they also experienced rationing, hardship and privations, certain categories of the population did manage to avoid starvation and, as restaurants were open, were still able to enjoy behaviours of their previous life.

In the Album du siège, Cham depicts a manservant informing his lady, reclining languidly in a chair, that her horses are ready – on the dinner table. A print of Paris assiégé shows a helpful manservant jovially reassuring his mistress, a marchioness surrounded by her domestic ménagerie (dogs, cats, fish and birds) that with such an entourage, she need not fear hunger…

In Paris assiégé, Draner depicts an officer introduced by an elegant “baroness” into a wealthy salon.

His New Year’s gift consists of an armful of goods and provisions that he calls “highly unusual objects”.

These curiosities include a rabbit, a duck and a leg of ham; a basket of vegetables; gruyère, fresh butter, asparagus, lard, canned peas; and a bag of coal…

If walking the street with a large chunk of bread under your arm plays to the French stereotypes, in 1870 besieged Paris, this becomes both a flaunted luxury and a necessity for those who can still afford to go out for dinner… In the Album du siège, Cham portrays a man wearing a top hat, dressed up to eat out in the city, who proudly carries a large chunk of bread under his arm. Similarly, in Paris bloqué, Faustin depicts a fancy couple, accompanied by their dog, carrying a piece of bread while going out for their “dîner en ville”. Several caricatures thus refer to a new restriction: even fancy restaurants did not serve bread anymore (while a complimentary basket of bread is still expected nowadays in any French restaurant), so that customers now had to bring their own.

In a print also entitled “Le rationnement du pain”, in the Paris assiégé series by Draner, an elegant couple enters a restaurant. A note on the wall indicates “les clients sont priés d’apporter leur pain”. An officer confirms to the waiter that he brought both bread and dessert. It probably alludes to his pretty companion, given that the officer is asking for a private room in the restaurant. Gluttony and lechery walk hand in hand.

As hunger was rife, even the starved zoo animals of the Jardin des plantes were killed and sold as meat to those who could afford it…

— Heidelberg UL, vol. 2 p. 111 and 196 ; Cambridge UL, KF.3.10

In an illustration by Cham for the Album du Siège, a bear and a lion join the long queue at a butcher’s. In Paris assiégé, the human-size elaborate and lengthy “Menu du jour” of the “Restaurant du siège de Paris” is presented by a jovial cook, with a gun on his back, in a spirit of patriotic resistance and defiance. It features goldfish (“poissons rouges au bleu”), angora cat (“gibelotte d’angora”), rat (“salmis de rats collecteur), elephant (“pieds d’éléphant, poulette”), camel (“bosse de chameau à la Bismark”), monkey (“côtelettes de singe parées à la Parsigny”), donkey (“oreilles d’âne à la Frossard” – after a defeated French general) and poodle (“gigot de caniche à la Sanfourche” – after a famous veterinarian). The sophistication and poetry of the phrasing as well as the reference to established dishes, sauces and animal parts (peppered with political references), contrast with the grim reality of the unusual meat on offer…

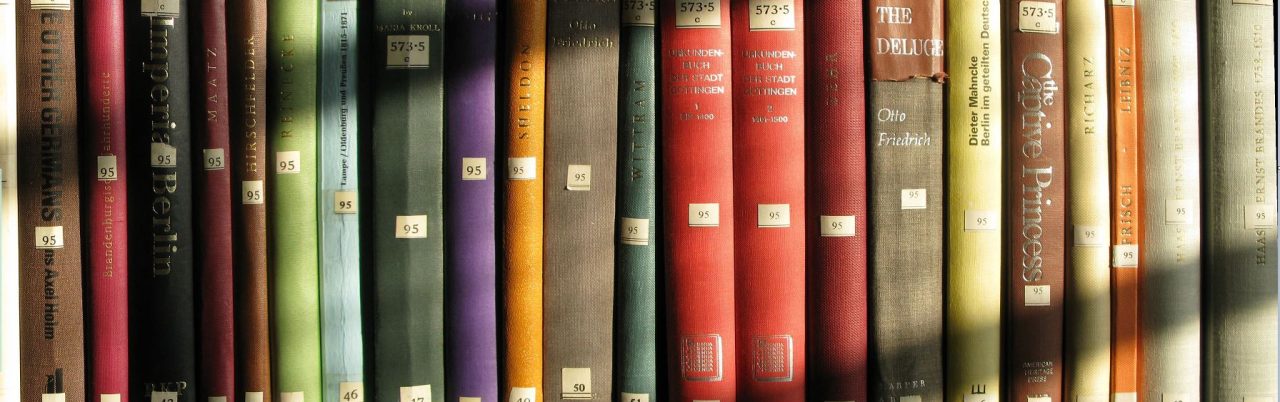

Food scarcity led to all kinds of embezzlement; substitutions were offered under false pretences. In Paris bloqué, a lady wonders at the calf’s head advertised on the menu, but the waiter confesses that it is actually a horse’s head (a fantastic object: “de la tête de veau de cheval”). In Paris assiégé, behind his shop windows, where tins of “beef” are attracting an eager crowd, a plump grocer smilingly points to a cat hidden from their view… The crisis was also an occasion of profit for some.

What do these caricatures tell us about the perceived evolution or persistence of inequality and class distinctions in besieged Paris? Though the rich were affected by the same shortages as the general population, and had to scale down and amend previous habits of consumption, the prints seem to point to the persistence of privileged lifestyles. Times had changed though, and in many caricatures, men, whatever their occupation, seem to wear the uniform of soldiers or gardes nationaux. While the satirical prints make fun of the way the wealthy managed to avoid food privations, they also raise ethical questions and highlight corrupt behaviours. If under the siege, all Parisians were united against the Prussian foe, social and political divisions would nevertheless shortly lead to a civil war, with radical social changes about to take place under the Commune government.

Irène Fabry-Tehranchi

References: Digitised collections of Franco-Prussian caricatures

Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris (legs Quentin-Bauchart)

Victoria and Albert Museum, London